Every body has a story.

SUBSCRIBE to receive new post notifications!

We will never sell your email address or other personal information to anyone.

Every body has a story.

Every body has a story.

Affiliate Disclosure: if there are Amazon affiliate links or other affiliate links in this article and you buy something through one of these links, I may earn a small commission. It will not increase the cost of your purchase. Thanks!

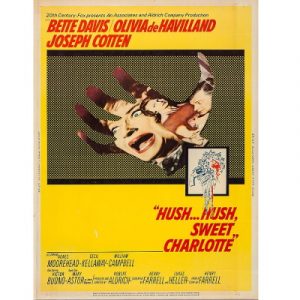

Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte

Movie synopsis with commentary

*** Warning! Spoilers Galore! ***

Content warning: this article contains potentially disturbing content, including references to macabre death and dismemberment, insanity, and abuse. Please use your best judgment as to whether you wish to read this content. Language is PG-13.

Twentieth Century Fox’s big-screen film Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte was released in the United States nationwide on January 20, 1965. Starring an aging Bette Davis (only 56 years old at the time of filming, but considered prehistoric by Hollywood standards), Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (affiliate link) is a mystery/thriller/horror film in the “hagsploitation” subgenre. (Hagsploitation is an indelicate word used to describe movies that star former box office A-listers of the female persuasion who have aged out of contention for the best film roles available.)

Charlotte starred many big stars of the day—Bette Davis, Olivia de Havilland, Agnes Moorehead, Joseph Cotten, George Kennedy, and Bruce Dern, plus several other “household names.” It was nominated for many awards, although the actors weren’t shown much love.

Bette Davis won the Laurel Award for Best Female Dramatic Performance. The only other “major” award for which she was nominated that year was the Laurel Awards’ “Female Star” category. She came in 11th out of 15. Agnes Moorehead was also nominated for a Laurel Award, in the Best Supporting Actress category, losing to Mary Poppins’s Glynis Johns. Moorehead was the only member of the cast nominated for an Academy Award (Best Actress in a Supporting Role), although she lost to Lila Kedrova (Zorba the Greek). Moorehead won that year’s Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress (beating out Lila Kedrova; Glynis Johns wasn’t even nominated).

The song “Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte,” written by the legendary and prolific Frank De Vol (music) and the not-as-legendary-but-should-be Mack David (lyrics), was nominated for an Academy Award for “Best Music, Original Song,” and a Laurel Award for Best Song (losing to Mary Poppins’s “Chim Chim Cher-ee” on both occasions). De Vol was also nominated in the Academy Awards’ “Best Music, Substantially Original Score” category, but again lost to the Mary Poppins (affiliate link) songwriting team of Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman.

Other Academy Awards nominations (and to whom they lost):

–Joseph F. Biroc for Best Cinematography, Black-and-White; winner: Walter Lassally for Zorba the Greek,

–William Glasgow and Raphael Bretton for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Black-and-White; winner: Vasilis Fotopoulos for Zorba the Greek,

–Norma Koch for Best Costume Design, Black-and-White (Koch had won the trophy two years earlier for What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?); winner: Dorothy Jeakins for The Night of the Iguana,

–Michael Luciano for Best Film Editing; winner: Cotton Warburton for Mary Poppins.

Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte did win the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Motion Picture, which was awarded jointly to writers Henry Farrell (story) and Lukas Heller (screenplay). That’s it for major awards.

Joan Crawford was originally cast in the role Olivia de Havilland ended up playing. The movie-makers were trying to cash in on the success of the film What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (affiliate link), which had been a box office hit for the Crawford-Davis team in 1962. For their work in Baby Jane, Davis had been nominated for a “Best Actress in a Leading Role” Academy Award, a “Best Actress-Drama” Golden Globe Award, a “Top Female Dramatic Performance” Laurel Award, and a “Most Popular Female Star” Photoplay [Magazine] Award (she won only the last one). Crawford was nominated for only one major award, a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award nomination for Best Foreign Actress, which probably didn’t appease her much, since Davis was also nominated for that one. So, as any industry icon and role model would do, after Crawford heard that Davis had been nominated for an Oscar while she had not, Crawford spent much of her time and effort during the following few weeks sabotaging Davis’s Academy Award chances. Although Crawford had already won a Best Actress Academy Award (in 1946 for Mildred Pierce) , Davis had already won two (in 1936 for Dangerous and 1939 for Jezebel). A third win would have made her the first woman ever to achieve that honor. (Ingrid Bergman ended up being the first, in 1975.) Not only did Crawford do whatever she could to influence the vote, she also pressured Anne Bancroft (nominated that year for the role of Annie Sullivan in The Miracle Worker) to let her accept the award for her if she won. Bancroft won. Either because she was too busy with the role she was playing on Broadway, or she was a really good friend, or she was just as afraid of Joan Crawford as most others in the industry were, she agreed to let Crawford accept the award on her behalf. I’ll bet Bancroft was off Bette Davis’s party invitation list for life.

[If you care—or even if you don’t—these were the winners of the other awards Davis and Crawford lost out on that year: the Best Actress-Drama Golden Globe Award went to Geraldine Page for Sweet Bird of Youth, the Top Female Dramatic Performance Laurel Award went to Lee Remick for Days of Wine and Roses, and the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress went to Patricia Neal for Hud.]

After that, many people were surprised that both Davis and Crawford consented to work together again…but working together isn’t exactly what either of them had in mind. There are all sorts of stories of all kinds of shenanigans the “ladies” got up to during filming. Said stories are probably not all true, but the following is an assortment of the more believable ones.

Crawford allegedly demanded top billing before she agreed to take the role. Davis allegedly agreed to second billing as long as she got paid more—a reported $200,000 salary, which was a lot of money back then. The financial arrangement Crawford allegedly agreed to was $50,000, plus $5,000 in living expenses, plus 25% of the profits—so she probably would have ended up with a substantially larger paycheck than Davis in the long run. However, Davis was also given a producer credit. Since she felt that the title made her queen of the entire production, she used the power to control whatever she wanted. To her, that power was probably priceless.

(As a zing toward Davis, Crawford had negotiated a contract amendment that included a clause stating that she and Davis would not have to appear together in any of their promotional appearances for Charlotte—although that turned out to be a moot point.)

Filming for Charlotte began on June 1 in Louisiana, where several outside scenes were to be filmed. Most of the cast and crew had arrived there on May 30, while Crawford arrived there on June 2 in order to begin filming the following day. According to some sources, in those few days between May 30 and June 3, Davis managed to buddy up to the crew by eating lunch with them and generally not treating them like the pariahs she probably thought they were. Once Crawford arrived, Davis furthered the divide by arranging fun field trips, inviting absolutely everyone—except you-know-who. This caused Crawford, generally known for her professional behavior and courtesy to all on the set, to become withdrawn and spend much of her off-time in her trailer. Ironically, Davis had won the Hollywood Women’s Press Club’s Golden Apple Award the previous year for Most Cooperative Actress.

[Actress Celeste Holm claimed that she received rude treatment from Davis when the two met for the first time, on the set of the film All about Eve . Holm said, “Good morning,” to Bette Davis, and Davis replied, “Oh sh[oo]t, good manners.” Holm claimed she never spoke to her again (which seems an excessive reaction, even for a sensitive soul). Davis wasn’t left with fond memories of Holm, either, later saying, in effect, that Holm’s personality was the only negative thing about the Eve experience.]

Allegedly there were also “Cola Wars” on the set of Charlotte. Crawford was the widow of Alfred Steele, who had been the President of Pepsi Cola, and she was still on the company’s board. She had Pepsi machines installed liberally throughout the work area. Davis arranged to have Coca Cola machines installed as well—and not because she had any connection to the product.

Allegedly Davis would also loiter near the director while he was filming Crawford-without-Davis scenes, loudly voicing her negative opinions about the goings-on.

Perhaps the unkindest cut of all, at least in Crawford’s mind, was the fact that Davis wouldn’t stop mentioning Crawford’s age (60, as opposed to Davis’s youthful 56).

Filming wrapped up on June 12. Crawford and Davis were required to work together for only the last three days of those two weeks. Allegedly on the afternoon of the 12th, while Crawford was napping in her trailer, waiting to see if she was needed for any last-minute shots, the rest of the crew packed up lock, stock, and barrel and went wherever they were supposed to go, leaving Crawford and her maid there with no vehicle/transport out. Crawford somehow managed to extricate herself from her predicament and get herself back to her California digs. Within 24 hours she had checked herself into the hospital, where she hid out was treated for a myriad of symptoms. (If she really had all of the illnesses that assorted sources—including Crawford herself—claimed she had, it’s unlikely she would have survived to film another day.)

Crawford was well enough after a five-week hospital stay to go back to work on July 21 (filming was by then taking place on a California sound stage). On the first day, Davis played nice, but on the second day she allegedly put on her Producer hat and slashed much of Crawford’s dialog from the scene they were about to start shooting. Crawford was not amused. Around this time Crawford decided that a half-day of work each day was about as much as she could handle and proceeded to leave work around noon for the next several days. Studio heavy-hitters consulted with Crawford’s attorney about the matter, and she managed to muster up the strength to put in a little more work for the next two days, but…mid-day on that second day, July 29, Crawford told the director (Robert Aldrich) that the heavier workload had taken too much of a toll on her and she needed to clock out for the day. The director waved goodbye to her and then shut down production until August 3. (“If you can’t beat ‘em….”)

The director had been pressuring Crawford to get checked out by the studio’s doctor. She finally relented, only to have him inform Aldrich that, while Joan was indeed ill with cold-like symptoms, she should still be able to work full workdays. (I can just picture Crawford thinking, “We’ll see about that!”)

Crawford one-upped both the doctor and the director by getting herself readmitted to the hospital on August 1. Aldrich waved his figurative white flag on August 4, stopping all production until further notice. Afterwards, he almost immediately started looking for a replacement for Crawford—probably going about it as quietly as possible.

Crawford was allegedly so ill at that point that she needed continued hospitalization, but she had enough energy to issue several press releases from her sickbed. She informed the public that doctors recommended she take at least a month to fully recuperate from her illness, which was allegedly a respiratory virus infection. She also informed the world that she assumed she would be replaced in the movie and recommended actress Loretta Young for the role. (Rumors at the time included 1) getting removed from the movie because of “illness” had been her plan from early on, and 2) she strongly encouraged other suitable actresses to turn down the role if offered to them.)

Bette Davis championed for her friend, Olivia de Havilland, to assume the role. De Havilland wanted no part of it—either that specific role or work in general at the time—but Robert Aldrich traveled all the way to de Havilland’s Swiss mountain hideaway and finally convinced her to take the part. The $100,000 paycheck might have had something to do with her decision.

Aldrich told Davis the good news, with a request that she keep the information to herself until he could arrange for the release of the proper announcements. He must have known she wouldn’t. She didn’t. Crawford heard it on the radio in her hospital room and “wept for nine hours”—even though she had expected to be replaced and had even made a casting recommendation.

Of de Havilland’s hiring, Crawford said, “I’m glad for Olivia. She needed the part.” Both statements were likely untrue.

There is photographic evidence that some of the other cast and crew members weren’t too heartbroken about Crawford’s departure, either. If one searches the internet, one can find a photograph of Davis, de Havilland, director Robert Aldrich, and co-star Joseph Cotten, all grinning and holding prominently displayed bottles of Coca Cola.

Lo and behold, despite the stress and anguish the ordeal had caused her, Crawford made a speedy recovery and was discharged from the hospital three days later, fully recovered enough to be to able start work on another project. Thus endeth the Davis-Crawford feud—at least in relation to Charlotte’s production. Allegedly the whole debacle upped the movie’s budget (lost production time, re-shooting Crawford’s scenes with de Havilland, etc.,) more than $700,000, to about $2.25 million.

Now, on to the movie itself:

In early May, 1927, melodramatic father and antebellum mansion-owner Sam Hollis (played by the versatile Victor Buono) is warning off his daughter Charlotte’s would-be fiancé, John Mayhew (played by Bruce Dern, with youthful looks and unmistakable voice). Hollis orders Mayhew to cancel his planned elopement with Charlotte, which Mayhew and Charlotte had scheduled for the next evening, during a grand ball at the Hollis home. Apparently, the day before, Hollis had discussed the situation with Mayhew’s wife (so “elopement” was a bit of a misnomer for what they had in mind).

As planned, the star-crossed lovers meet in the summer house, and, as ordered, Mayhew jilts Charlotte. She cries and cries, shouts the completely expected line, “I could kill you!” and storms off, all without ever facing the camera straight-on.

Cut to the next scene, where a servant is trying to open a small case of champagne with a meat cleaver. His boss stops him, producing a pry bar to do the job—although he doesn’t seem to have any better success than his assistant had. (Camera focuses on champagne case and cleaver). The next few snippets of film establish that 1) Mr. Hollis is no longer among the throng of party-goers, 2) the cleaver has disappeared, and 3) it had not been taken by either of the two workers.

Back in the summer house, Mayhew is alone (aside from two noisily chirping caged birds), feeling sorry for himself and clutching the small flower nosegay Charlotte had left behind. A silent, decidedly-not-Charlotte-shaped shadowy figure enters and…now we know where the cleaver went. Mayhew is relieved of his earthly burdens, as well as a couple of body parts.

A bit later Charlotte walks into the ballroom, staying in the doorway and somehow managing to keep her face in the shadows, and the room falls silent, including the band (played by the talented Teddy Buckner and His All-Stars). Charlotte’s gown has a big ol’ splotch of blood front and center, with drips all the way down to the floor-length hem. (Blood-spatter experts should not analyze the placements too closely). Mr. Hollis is there, splotch-free.

The next scene takes place in 1964, at the Hollis mansion. A group of boys about 10-14 years old is walking up to the place, taunting the “new boy” (played by John Megna-article link), to go into the “haunted house” and take something Charlotte had touched, in order to be allowed into their club. (They pass by the small family cemetery and Mr. Hollis’s tombstone—apparently he had only survived for about a year after the bloody ball, dying at the age of 45-46.) The boy enters the house through the conveniently unlocked front door, gets startled by a grandfather clock that chimes one time when it isn’t one o’clock (or any “o’clock”), and walks right in front of the chair Charlotte is sitting in (presumably dozing). “Boy” opens the lid of the music box set on the table right next to Charlotte’s chair, gets scared by Charlotte’s presence (and vice versa), and gets out by finally managing to open a conveniently handy side door that appears to have been inconveniently locked (either that or he was just so panicky he couldn’t work the handle correctly at first).

While the credits roll, the boys sing a suitably eerie and surprisingly well fleshed-out song taunting Charlotte (chop, chop!” being a prevalent lyric) à la “Lizzie Borden Took an Axe….”

The next scene shows a man bulldozing Charlotte’s gazebo (not a euphemism). Charlotte (played by Bette Davis) jumps out of bed, grabs her shotgun, and proceeds to take a potshot at him from her second-story balcony. The man is part of a construction/destruction team, and the team’s foreman (played by George Kennedy being George Kennedy) gives Charlotte a piece of his mind, his southern accent wavering in and out by the word. He tells her that whether she likes it or not, she is losing her home to eminent domain, and her land will soon be the location of a bridge—for the greater good, of course. He promises her that she’ll soon be hearing from the sheriff. Charlotte tries to bean him by pushing a heavy flower pot off the balcony (in a lighthearted kind of way). She misses by a good three feet, but the sound causes Velma the housekeeper (played by Agnes Moorehead) to come a-walkin’. Velma has obviously seen Charlotte in similar moods before, and calmly cajoles her away from the tempting targets.

The foreman storms away, doing his best Yosemite Sam impression, and squeals on Charlotte to the sheriff, just as he said he would.

In town, a silver-haired gentleman stranger with a posh British accent visits the sheriff, pestering him for scuttlebutt about the decades-old Mayhew murder case (apparently Mayhew’s chopped-off head and hand haven’t been seen by anyone since they were still attached to the rest of him—except, of course, by the murderer). The stranger claims to be looking into a matter of an “unclaimed insurance policy”—as if that ever happens—but thinks that telling people he is a reporter for an “esoteric” true crime magazine might sit better with the locals. The sheriff, always on the side of law and order, says, “Whatever.”

When the sheriff comes calling on Charlotte, she tells him and Velma that she wants her cousin Miriam Deering to come and help her out of her predicament. The sheriff isn’t worried, but Velma doesn’t need to have magical powers to know that Miriam’s involvement can only end badly.

Of course, at that very moment cousin Miriam (played by Olivia de Havilland) is being transported by taxi to Charlotte’s doorstep.

Charlotte’s doctor (Dr. Drew Bayliss, played by Joseph Cotten) pays a house call on her. (Remember them? Me, neither.) He’s an old friend and also apparently a bit of a condescending bully.

Miriam shows up at the house, to the delight of two of the three people there—although none of them can resist commenting on the fact that she arrived a day early. She thanks Charlotte for the invite, and the two talk about old times, though Miriam seems a bit reserved.

At dinner, with the doctor, Miriam, and Charlotte in attendance, when the subject of the imminent destruction of the house inevitably comes up, it’s two against one. As soon as Charlotte hears that Miriam is of the mind that “you can’t fight City Hall,” Charlotte starts hurling insults at Miriam, reminding her that she came from a poor upbringing. Then Charlotte announces that she knows it was Miriam who told John Mayhew’s wife about their plan to run off together. The doctor seems taken aback by the news and steps away from the table. To Miriam’s credit, she admits that she told Mrs. Mayhew and Charlotte’s father, to get back at everyone for treating her like a “poor relation” that they had taken in out of the kindness of their hearts (which, in fact, was the case). More heated trash-talking ensues. Maybe the doctor moved away from the table because he didn’t want to be in the middle of the action if fists started flying.

Mayhew’s untimely demise is brought up. Charlotte gets distracted thinking about him and heads (pardon the expression) upstairs, calling “John? John?” as if she thinks he might actually answer. Her departure allows the now-alone twosome of the doctor and Miriam to freely discuss Charlotte’s mental stability and the fact that she’s just not quite unbalanced enough to be committed yet. The two had been in a relationship way back when. He had broken it off after/because of the murder, but they had kept in touch through letters. Miriam laments that Charlotte didn’t use any of her riches to fix up the house, but since the place is going to be firewood by the end of the following week, it seems that maybe Charlotte’s lack of action wasn’t so foolish after all.

The doctor gives Miriam a gun before he leaves for the evening, “just in case.” Let’s hope no young boys are planning any club initiations there that night. The doctor gives no explanation as to why he had a gun on him in the first place.

Miriam enters her room to find that somebody has slashed one of the dresses she had hanging up in the closet—presumably somebody with better taste in clothing than she has.

The nosy stranger, now identified as Harry Mills, is still poking around, this time finding out what the town’s newspaper editor can tell him. He can tell him this: no charges were ever brought against Charlotte, but the editor believes that the reason for this is because Hollis had friends in high places, not the official story claiming a lack of evidence.

Miriam goes into town, and the very first person she encounters is John Mayhew’s widow, Jewel (played by Mary Astor). Jewel is hopping mad at Miriam for her gossipy behavior 37 years before, but since Jewel is of frail health she settles for imparting a scathing tongue-lashing instead of the full-on smackdown she is so obviously yearning to deliver.

Back at the mansion, Charlotte is all riled up. Some stranger had put a not-esoteric true crime magazine in Charlotte’s mailbox, and Velma dutifully delivered it to Charlotte’s room. It’s possible that Velma didn’t notice the drawing of the headless, one-handed corpse taking up a good deal of space on the front cover. Or the huge photo of the Hollis mansion…or the prominent inset of a young Charlotte’s picture.

Charlotte tells Miriam that Jewel Mayhew put the magazine in the mailbox. When Miriam protests, saying Jewel is in too poor health for the activity, Charlotte produces dozens of poison-pen missives, declaring that she was sure that Jewel Mayhew had been the one sending them to her for decades. (The only one shown on camera just has “murderess” written on it in very nice cursive.) There’s no mention of envelopes, postage, or postmarks.

The nosy stranger has finagled an invitation to tea from Jewel Mayhew. She talks about her bad health and her lack of money, and then entrusts him with an envelope that contains some information she thinks is important. She asks him not to open it until she’s gone (as in dead), and then do with the contents whatever he thinks is the right thing to do. He mentions her “policy with Lloyd’s,” so maybe there really was an unclaimed insurance policy. We’ll see.

Back at the mansion (again), Miriam is awakened in the middle of the night by the sounds of Charlotte singing downstairs. Miriam goes to investigate, and by the time she gets there, Charlotte is crying and being wishy-washy about just how dead John really is. Then a cloud(?) shadow moves away from the window, letting in enough moonlight to reveal a meat cleaver with the tip of its blade lodged in the floor, a disembodied hand, and something that looks like a wet rat but is probably supposed to be a nosegay similar to the one Charlotte had carried at that long-ago ball. Exit Charlotte, stage right, with Miriam following closely behind. After a bit, Miriam comes back downstairs in the dark to take a quick peek at the scary paraphernalia, but of course it’s nowhere to be seen.

The next morning, Charlotte checks out the same spot, but in the light of day she can see that the wood floor shows obvious signs of damage at the spot where the cleaver had been stuck in it the previous night.

The nosy Harry Wills (if that’s his real name) shows up at Charlotte’s house, and she’s surprisingly courteous to him. (Velma keeps on giving him suspicious side-eyes from afar.) Mills claims he was one of the gaggle of reporters trying to get a story from Charlotte when she first got to England, where she had fled after the murder. Charlotte says she didn’t talk to anyone at that time, so as proof of his assertion he describes the outfit she had been wearing that day. (Just because she wouldn’t talk to anyone doesn’t mean no one had taken her picture, so he still could be lying.) Mills asserts himself as an “authority” on her, saying it in a way that makes himself sound more like an ardent admirer and less like a stalker. Potato, potahto.

Miriam had arranged for some local women (one of them played by veteran character actress Lillian Randolph) to pack up the household goods, and when Charlotte sees one of the strangers holding her beloved music box, she snatches the box from the women and orders all of them out. Miriam comes in and tells the women to wait for her outside, while Charlotte accuses Wills of snooping around the place, looking for Mayhew’s hand. She taunts him by saying that maybe she keeps it in the music box she’s still holding, but we all know she doesn’t because the background music isn’t scary enough. Charlotte says the music box—and the song it plays—had been gifts from Mayhew, which explains her fixation with it. Miriam tells Wills to go, blaming him for Charlotte’s meltdown, not the unfamiliar women roaming around Charlotte’s house and moving all of her stuff.

That night there’s a violent thunderstorm. Charlotte rushes out onto the balcony, apparently wanting to play Russian Roulette with the lightning. Looking down, she sees a man walking across the front terrace, parallel to the house. The storm wakes Miriam as well, and her borrowed gun is clearly lying on the nightstand next to her, as if she’s daring someone to take a potshot at her while she sleeps. Charlotte rushes downstairs and sees the man’s shadowy figure pass by a window on the front porch. She then rushes outside, only to hear someone playing her grand piano inside. Movie-watchers are privy to a brief clip of the hands of someone wearing a man’s suit and playing the piano (with two hands, so it probably isn’t Mayhew’s ghost), but of course poor Charlotte doesn’t see this because she’s still outside. Charlotte runs to the closed double doors of the music room, and the music stops the very second she opens the doors. There’s no one inside. Human or ghost, that piano player moves fast. She shuts herself in the room and calls hopefully to Mayhew. Meanwhile, Miriam gets up, sensibly shutting all the doors Charlotte had opened. Little middle-aged Miriam manages to break open the music room’s locked doors, which Charlotte had shut herself behind, and finds that all the mirrors in the room have been smashed and Charlotte has a bloody injury to her wrist. Charlotte blames her father, saying he still hasn’t forgiven her. Miriam says it wasn’t him (and I have to agree with her on this one).

Miriam gets Charlotte tucked in for the night, and bright and early the next morning Miriam and the doctor tell Charlotte (who is still in bed and confused about what had transpired the previous evening) they are going to take her somewhere she’ll be “comfortable.” Charlotte’s all worried that Jewel Mayhew will see her being carted off, while she probably should be more concerned by whatever it is the doctor is injecting into her arm.

Out of Charlotte’s presence, Miriam sacks Velma and the two get into an accuse-a-thon. Velma says Miriam is plotting against Charlotte, and Miriam says Velma is plotting against her. The doctor enters the fray and sides with Miriam, to no one’s surprise, so now Velma accuses them of working together. Velma hightails it to wherever Harry Wills is and asks him to intervene. He meekly says, “But what can I do?” and proceeds to do nothing.

Charlotte goes into her father’s study and has a very sane conversation, even though she’s talking to her dead father (whom she believes to be the real murderer). She hears a knock on the front door, and when she uncharacteristically opens the door wide without even taking a peeking out of one of the many nearby windows to see who it is, a low-brow journalist starts taking photos of her. She stands there in shock, and he leaves after a few shots. After his departure, Charlotte closes the door and turns to face the stairway. Miriam comes to the top of the stairs, holding a box, which just happens to open and spill its contents—John Mayhew’s head. It bounces all the way down the stairs, coming to a rest at Charlotte’s feet. He looks pretty good for a guy who’s been dead for 37 years.

With Velma out of the house, Dr. Drew and Miriam don’t have to keep up any pretenses about their true motives, and go about discussing their plans to take over the estate, talking across Charlotte’s bed while she’s lying in it, drugged. Miriam’s holding the fake Mayhew head that Dr. Drew’s artist friend had made at his request. Everything’s coming along very nicely for the two of them, thank you very much.

Velma sneaks into the house very quietly—until she accidentally knocks a vase(?) to the floor, alerting Miriam that something is amiss. Fortunately for Velma, Miriam doesn’t have the same penchant for running all over the house and flinging doors open that Charlotte does, so after just a few bemused glances around, Miriam picks up the broken pieces and walks off in the opposite direction from the room Velma is hiding in.

Velma manages to make her way to Charlotte’s room unnoticed—tiptoeing in an exaggerated, almost comical way. She finds the syringe and medicine vial on Charlotte’s nightstand. She sniffs the vial and says, “That’s some kind a drug, isn’t it?” Ya think?

Velma gets Charlotte’s coat and starts to help her out of bed, but then she hears someone approaching and undoes everything she just did, except…Miriam enters the room to fetch Charlotte’s breakfast tray (which Charlotte hadn’t touched because, well, she’s drugged practically into a stupor). Miriam doesn’t see Velma because Velma had hidden in the closet, but she does see that the medicine vial is missing. (To drive home the point, the filmmakers zoom in on the table where the now-missing vial had been, then fade in the bottle and fade it out again.) Yup, it’s not there anymore.

Tipped off by the fact the vial is missing, Miriam catches Velma in Charlotte’s room. The two women in the room who are conscious play a little cat-and-mouse game, and for a change Velma wins—for a moment. Velma darts out of the room, but Miriam confronts Velma at the top of the stairs, and…wait for it…courtesy of Miriam’s well-aimed chair to her head, Velma ends up at the bottom in a lifeless heap, to no one’s surprise, except, surprisingly, Miriam’s. She calls Dr. Bayliss (Dr. Drew to his friends), who comes to the house. He acknowledges that Charlotte’s father was, in fact, not the person who lightened John Mayhew’s load (although he doesn’t continue on to say who he thinks did). Miriam responds as though she already knew that Hollis wasn’t guilty, and at the moment she is more concerned with the fact that she just murdered someone. The doctor assures her that no one will know it wasn’t an accident—except for him, and implies that, in light of this, maybe a little extra financial compensation for him wouldn’t be remiss.

Mr. Wills goes to the funeral parlor, where the funeral director (played by Percy Helton) tells him that Velma’s demise had been caused by a fall off a ladder at her own pitiful excuse for a house. When the funeral director goes on to tell him that he didn’t know who had reported the incident, but that Dr. Bayliss had been the one to bring her in, Wills senses something is afoul. Too bad his epiphany comes too late to help Velma.

When Charlotte is in bed that night, the dastardly duo start calling out her name in a spooky, echo-y manner. The doctor then sits at the piano and starts playing “Charlotte’s” song, eventually singing the lyrics that apparently everyone knows, even though they were gifted to her during an illicit romance.

Charlotte, of course, thinks the music maker is Mayhew, even though she thought she had seen his head bouncing down her staircase just a night or two before.

By the time Charlotte gets to the piano, no one is there, so she plinks a few notes of the song on the keys before she notices a gun inside the open baby grand. Charlotte picks it up and hallucinates that it’s a nosegay (as one does), imagining that she is back at that fateful ball in 1927. She and “Mayhew” dance (he hasn’t aged a day) until her father shows up. Mayhew backs away, out of her imagination, and a few seconds later her fantasy collapses. “Mayhew” reappears, first intact and then as he was last seen. Charlotte isn’t so keen on this version of him, so she shoots at him with her nosegay, which does a pretty good job of stopping him, considering that in her mind it’s a bouquet of flowers.

Charlotte snaps out of it to find that she’s shot her doctor. Miriam is distraught that the doctor is dead, (although it seems like the best thing that could happen for her). Charlotte offers to pay Miriam if she helps her hide the crime, and all of a sudden Miriam sees that things are looking up.

Just then Harry Wills shows up. It’s still the middle of the night, but he knocked on the door anyway because he saw the lights were on. Miriam talks with him briefly while Charlotte stays out of sight, watching the doctor’s body slowly tip over toward the front hall from the spot where they had leaned him against the wall. Miriam gives Wills the bum’s rush just in time, and then Miriam and Charlotte argue about who’s helping whom (probably not the best time for bickering, ladies). Miriam takes Charlotte and the doctor to a pond or lake and forces Charlotte to help her push the body down the hillside. They drive back home, Miriam slaps Charlotte around a bit for good measure, and then orders her to go to her room.

Charlotte crawls up the stairs evvver sooo slowwwly, and at the landing she encounters poor, dead Dr. Drew standing there, all muddy and disheveled from his time in the drink. Charlotte crawls back down the stairs evvver sooo slowwwly, where the conniving Miriam is there to console her.

The next evening (probably), a dolled-up Miriam greets a not-dead-anymore Dr. Drew on the front terrace. They have a refined disagreement about which one of them should be the “senior partner” of their relationship—her, because she’s smarter, or him, because he knows how clumsy old Velma really died.

Miriam surprises a getting-tipsier-by-the-sip Drew by telling him that it was she, not Jewel Mayhew, who sent Charlotte all those poison pen notes. She surprises Drew and the audience by saying that she had seen Jewel Mayhew sneak to the summer house the night of the ball, and Jewel had been paying Miriam hush money all these years. That would explain why Jewel was so nasty to Miriam when they met in town, but not why Jewel thought that a blackmailer was somehow a more despicable person than a husband-beheader.

While Miriam and the doctor keep on congratulating themselves for the success of their brilliant plan, a seemingly coherent Charlotte comes out of her room and eavesdrops on them from the upstairs balcony. Drew tells Miriam that the people from the state institution are coming there in the morning to take Charlotte to that place where she’ll be “comfortable.”

Charlotte sees them hugging and hears them gloating about their accomplishments and slandering the two people she loved most in her life, her father and John Mayhew. When Miriam comments that she would like to see the look on Charlotte’s face when the still-living Dr. Drew shows up at the facility to concur with their medical team that Charlotte is indeed insane, Charlotte pushes a heavy planter off the railing. Apparently her earlier go at the construction foreman was good practice, because that second push is a two-fer.

The next morning there are many townspeople loitering on Charlotte’s front lawn to keep watch on the goings-on at the house, where the local authorities are collecting Charlotte for her trip to wherever they think she should be going. A few ladies in the yard are gossiping (including Grandma Walton and Mamie Baldwin, Ellen Corby and Helen Kleeb). Of course, their “facts” are mostly wrong—as gossip usually is—but they probably don’t care, as long as it’s scandalous. One thing they discuss that is true is the fact that Jewel Mayhew had dropped dead of a stroke that very morning.

Harry Wills shows up on the scene with the low-class photographer, and Wills tells him about the Jewel/Miriam story, leaving Miriam’s name out of it and phrasing it in a “what if” fashion. He speculates that Jewel might have abandoned the life insurance policy because she didn’t want anyone investigating her husband’s death too closely.

Charlotte comes downstairs, overdressed for where she’s probably headed, carrying her beloved music box. Before she walks out the door she puts the music box down on a side table. It seems she’s already a little bit saner. Maybe she’s buoyed by the fact that at least Jewel Mayhew won’t be outside to witness her indignity.

As she’s sitting in the back seat of the car, waiting to be driven away, Harry Wills gives her the envelope Jewel Mayhew had entrusted to him. Charlotte reads the enclosed letter, and looks a bit shocked by its contents. As she is being driven away from her house (ostensibly for the final time), she’s gently waving out the window to Wills and the sheriff—using the hand with which she’s holding the letter. She’s taking a pretty big risk with the one thing that might make the difference between eventual freedom and being locked up forever. The letter doesn’t get blown away, so she’s got a chance—but we’ll never know for sure because right then, the end credits roll. Singer Al Martino performs “that song,” so the audience finally gets to hear it the way it was supposed to sound.

The whereabouts of Mayhew’s missing pieces are never revealed, but it’s fun (for the more macabre-minded of us) to imagine a scene where some unsuspecting house cleaner discovers a surprise when emptying out Jewel Mayhew’s bedroom closet.

If you or someone you know is or may be experiencing abuse or violence, please call your regional or national abuse protection helpline. In the United States, the national Disaster Distress Helpline is 1-800-985-5990.

Other resources are also available:

National Child Abuse Hotline: 1-800-422-4453 (4-A-CHILD)

National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE); TTY 1-800-787-3224

National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-4673 (HOPE)

National Teen Dating Violence Hotline: 1-866-331-9474; Text “loveis” to 77054

State Resources at the Administration on Aging, National Center on Elder Abuse

If you or someone you know is struggling with depression or addiction, please call your regional or national substance abuse and mental health helpline. In the United States, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration’s 24/7 National Helpline is 1-800-662-HELP (4357).